The London based, Iranian Bijan Daneshmand tells art journalist and writer Lisa Pollman about his work and how it's inspired by Persian architecture and mathematical principles.

|

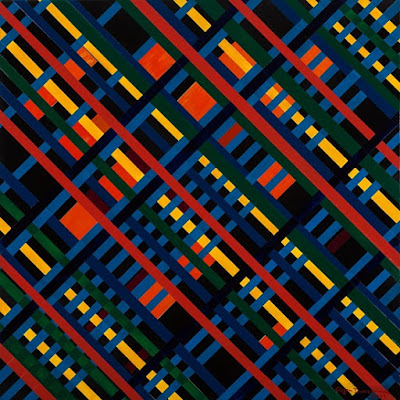

| Bijan Daneshmand, Rood, 2016, Oil on canvas, 122 x 122 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

From my teen years on, I enjoyed drawing and had an interest in structures and buildings - both in terms of how they were built and their aesthetics. I chose Civil Engineering as a degree at Kings College London.

I was inspired by Mondrian and the De Stijl Movement, and later by Frank Stella and Agnes Martin. In particular, I was inspired by the grid type patterns, hard edge finish and solid areas of paint. Rather than say the education or my occupation impacted my work, I would say that I entered an occupation and pursued work that I found interesting and aesthetically engaging. Many years later, I pursued a MA in Fine Art at Chelsea mainly to find direction in my practice.

Explain your interest in Persian architecture. Are there any particular facades that you admire? Which ones?

I have a special feeling for the architecture of my country in both the larger cities of Isfahan, Yazd and Kashan as well as the smaller towns and villages such as Natanz, Nishapur, Gonbad, and Abyaneh. Throughout Iran we have creative and intricate buildings: garden houses, tea houses, private houses, government buildings, palaces and mosques that date from the Persepolis (6th century BC) to later works in the 13th and 14th centuries. More recent works from the Qajar and Pahlavi eras are also of interest.

Persian architecture displays strength in structure and aesthetics. I would say the most notable areas of inventiveness and originality are in our arches, vaults and domes and further demonstrated through the use of ghanats (groundwater systems) and wind towers for cooling. Some argue that the greatest Persian artform has been our architecture and represents the highest and truest expression of our civilisation. I would add poetry to that.

If I were to compile a list of favourites, it would include Naghsh-e Jahan Square, Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, Ali Qapu palace, Chehel Sotoun in Isfahan and the Borojerdi and Tabatabaei houses in Kashan, and various buildings in Yazd. So many to mention! Beautiful works, which also function, that you could look at all day.

Can you please tell us in your interest in A Mathematician's Apology by G.H Hardy, 'a mathematician, like a painter or poet is a maker of patterns. I am interested in Mathematics as a creative art'. Are you a mathematician or an artist? Or both?

This quote resonates with me. I like the purity of math. I am not a mathematician but use some basic math and geometry at the starting point of my work. After that, I allow the work to take place, be organic, and to have a life of its own. I have found there is less control once the work has begun.

I do find scientists and their discoveries fascinating. In particular, I am interested in their theories about the world, the universe and how possibly it began. The sizes are incredible - how tiny we are and how huge and endless the universe is!

Please give us a brief background on the tiles that Sir Roger Penrose discovered and how this type of patterning is displayed in your work.

In 12th century Persia and various other countries adapting the same architectural influence, Girih tiles (sets of five tiles) were used to decorate buildings. Their arrangements significantly improved with the Darb Imam shrine in Isfahan around 1450-60. They are basically a decagon, a hexagon, a bow tie, a rhombus, and a regular pentagon, all five figures having the same length on their edges. Girih, meaning “knot” in Persian, are lines found on the foreground of the tiles.

Sir Roger Penrose proposed in 1974 that a set of two tiles (being a fat and thin rhombus, or a kite and a dart), when arranged, follow a certain set of rules and force aperiodicity.

In 1982, Dan Shechtman discovered the Icosahedral phase, opening up the new field of quasi-periodic crystals, and was awarded the Nobel prize in Chemistry (2011).

These crystals form structures in a manner similar to the three dimensional analogues of Penrose tilings. Hence, 13th century Persian architecture, 1974 math, and the structure of Quasicrystals- all exhibit extraordinary aesthetic properties and are unique every time.

In 2007, Dr Peter J. Lu of Harvard and Paul J. Steinhardt of Princeton wrote a paper stating that the Girih tiles of around year 1200, and particularly those seen at Darb Imam, closely resemble Penrose patterns. They were astonished to find that the tiles formed a near perfect Penrose pattern. The craftsmen, the architects of that time in Persia, and the Persianate region, were designing and constructing complex geometric patterns. The question arises behind what kind of mathematics or systems they were using to help them set out these intricate and complex designs.

Your website states that your practice is “concerned with repetition, difference and disruption”. What techniques do you employ to add aspects of disruption to your work?

To me, everything is involved in a repetitive cycle - the cosmos, the motion of the planets, day, night, and all the cycles we see everyday. However, there are disruptions, eruptions, quantum leaps, things happening and new routes are opening up. We become who we are through repetition; repetition consolidates our character, our habits and addictions.

I try to use the simplest idea. There is something spiritual in that and not complicated. For a number of years I was painting triangles. Other than the circle, the triangle is the simplest shape, consisting of three straight lines. Then for a period I was painting lines, lines over lines, or interwoven lines. Subsequently, I worked on dots, or circles. I repeatedly painted or drew the same idea, or thing. Every single shape was always different. No two are ever the same.

When ‘painting’ or ‘drawing’ takes place, similar to an event taking place, at a moment, or at moments, due to all the differences, we see disruptions taking place. There is an event, a happening. Therefore, I don’t need a technique to add aspects of disruption; as the work happens the disruptions are naturally created. To avoid the disruption I would require a technique to force it not to take place. In sum, the entire process is important for me.

You state that “in every action of repeating there is a birth”. Does that mean there is also a death? Please explain.

With every repetition, there is a birth. French philosopher Gilles Deleuze claims that ‘true repetition is the repetition of difference, eternally reaffirming the creative difference of life’. As soon as something is born, its death is created. Death is always there. It is always a possibility, about to happen. However, it may not happen for some length of time, but it does eventually happen. So there is birth and death, always.

Usually when discussing repetition, people talk about boredom and death. But there is repetition and there is repetition. By this I mean we need at pay attention. By repetition I am not talking about duplication. Take a game, like tennis. Every game played is different. Of course the rules, the court size, racquet specification, the balls are predetermined, but no two points, no two games, no two matches are ever the same. We can apply the same idea to any activity. Even making a spot with ink on paper, or drawing a simple circle, again and again. It’s never the same.

So, if we are attentive, present, we will not be bored, we would actually see a birth every time, in the simplest of observations. From the leaves of a tree to whatever you would like to choose. Death here is ‘not being there’; no attention, no presence. Death as a word used in the normal everyday sense refers to a change of state. We die, and change state, and no longer exist in the physical form. That is the death of not being present.

What rules and limitations do you impose upon your work?

I choose to work on a simplified notion, still allowing numerous possibilities. No need to complicate things unnecessarily. Narrowing down and adopting self-imposed boundaries helps my creative process. For my work, rules and limitations are adopted at first, they help the works to commence. They are not rigid and often are abandoned. There are various methods; they are useful for the making. I seek to express through a visual experience a practice that is engaging and affective.

The limitations I set on my work usually involve the shape, structure and application of the medium. To start off a painting, a drawing or a structure a set of rules are adopted. I then allow it to have freedom, a life, to be organic, to flow and find its way. When there are no rules and limits, an infinite space from which to work from, I can’t start anything. I find it distractive and indecisive. I find it useful to know I can use x, y and z and I have the resources a, b and c and get on with it.

In a catalogue forward from Helen Sumpter, she says that your work is orderly with a hint of being “chaotic”. Are both of these factors integral to your work? Why?

That is Helen Sumpter’s observation based on my 2008-2013 works. Those works could be initially described as accurate, orderly, obsessive. Upon closer examination, a common theme consisted of a foreground of lines overlaying and interweaving each other upon a fluid and chaotic background. I painted these works as a metaphor of our soul hidden by our ego. The soul being the fluid-like ground, and the lattices and grids of lines being the layers of our ego or the armour. Hence, I think that’s why she mentions orderly with a hint of being chaotic. In these works, both chaos and order had meanings to me.

Please tell us about your “mental convolutions” and how they are depicted in your work.

This remark was made by Sergio Spadaro. What is depicted in my work is a reflection of how I see and I am seen. Art is a self-portrait in one form or another. I believe we strive to be the true expression of ourselves as human beings. That expression may be artistic or other.

What are you working on at the moment?

I am making drawings and paintings using the fat and thin rhombus, kite and dart shapes, and the five Girih shapes from Persian medieval patterns. The simplicity of the shapes allows a huge choice of works and eliminates the questions as to what is to be painted and how will it be painted.

With these shapes, I enjoy a connection with my Persian roots, the link to modernism through the fact that the mathematics of these geometric designs were discovered in the 1970’s and the idea that Quasi crystals are also constructed with these patterns. I used to think that my art must transcend from where I came from. I used to think pure abstraction should have no reference or derivation from anything. Now I critique and observe these ideas.

For a series of paintings, I am currently working on, for example, I use the rhombii shapes, with specific angles. Sometimes I follow certain rules in setting out, other times I don’t. I draw as though I am fixing a physical object onto the canvas, allowing for the gesture and the human mark to be visible, and the disruptions to occur. None of it needs to be forced.

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Lotf, 2016, Oil on canvas, 122 x 122 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Scintilla, 2009, Acrylic on birch, 76 x 76 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Preweave, 2009, Oil and acrylic on birch, 76 x 76 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Cardinal, 2009, Oil and acrylic on birch, 76 x 76 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Sanguine, 2013, Oil on canvas, 122 x 76 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Iota, 2013, Oil on canvas, 76 x 122 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Green Yellow Peaks, 2013 , Oil on canvas, 180 x 152 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Doucement, 2013, Acrylic on linen, 76 x 51 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Blower, 2013 , Oil on canvas, 122 x 183 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Birkbeck, 2013 , Oil on birch, 76 x 122 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Bacarat, 2013, Oil on birch, 90 x 90 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Left White, 2015, Oil on raw canvas, 122 x 122 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

|

| Bijan Daneshmand, Black Right, 2015, Oil on raw canvas, 122 x 122 cm. Courtesy the artist and Janet Rady Fine Art. |

No comments:

Post a Comment