Nudity in contemporary art is tolerated increasingly in countries where it wasn’t in the past

by Barbara Pollack

Although the nude is widely considered a foundation of Western art history, this is clearly not the case in many other cultures around the world, where religious and social traditions often prohibit depictions of the body. Nevertheless, contemporary artists from many countries in the Middle East and Asia are now exploring nudity, sometimes to connect with erotic themes in pre-Islamic periods and sometimes as an act of open rebellion against social and political conditions. There has recently been a growing acceptance of work involving nudity, as many of these countries have developed their own contemporary-art markets. But in some places, especially Iran, the penalties can be formidable and frightening.

Challenging the censors is Ramin Haerizadeh, who, in his digital photo series “Men of Allah,” casts himself as a performer in a harem, cavorting naked in configurations reminiscent of Persian tapestries. Until 2009, he was able to make these works while living in his native Tehran. But when they were featured in “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East” at the Saatchi Gallery in London that year, Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and National Security began harassing local galleries to determine the artist’s whereabouts. They even raided a collector’s home, seizing several of Haerizadeh’s works and threatening the collector with four months in prison. Friends warned the artist, who was in Paris with his brother Rokni, a painter, for the opening of their show at Galerie Thaddeus Ropac. They never returned to Iran, fleeing to Dubai, where they now live and show with Gallery Isabelle van den Eynde.

To most viewers, Ramin Haerizadeh’s images would seem more whimsical and lyrical than provocative. In today’s Iran, however, where a strict reading of Islamic law forbids depictions of the body, an artist can face imprisonment or even execution for making such bold statements. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t artists in Iran, or other Islamic countries in the region, who incorporate nudes into their work. In fact, there are many, drawing upon influences ranging from Persian miniatures to Jeff Koons.

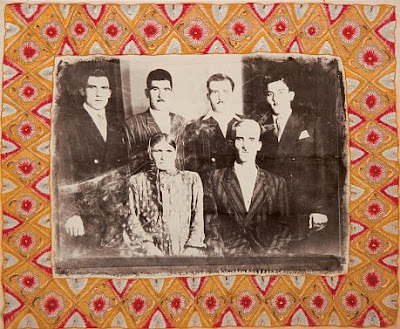

“There is a strong erotic tradition in Iranian art, such as art from the Safavid empire in the early 17th century that is full of erotic images, not all of them heterosexual,” says art historian Edward Lucie-Smith who, along with dealer Janet Rady, curated “Iranian Bodies” at the Werkstattgalerie in Berlin this year. “This was the point of doing the show—to demonstrate that there was a real continuity based on erotic feeling in Iranian culture,” he says. “Also to show that women artists in Iran are often bolder than the men.” The exhibition—which featured works by Haerizadeh, as well as psychedelic photo collages by Fereydoun Ave, paintings of people submerged in bathtubs by Mitra Farahani, mannequins pierced by and balancing on a bar by Narmine Sadeg, and surrealistic self-portraits by Nikoo Tarkhani—provoked outrage back home. Gholam-Ali Taheri, the head of Tehran’s Museum of Contemporary Art, denounced the work as “decadent,” and a story decrying the artists spread throughout the media, but the artists themselves were not harassed by the authorities.

Tarkhani, in her bold paintings, portrays herself as bald with her body fragmented against a backdrop of blue tiles. “I am not talking about Islam or any other religion,” she says. “I am only talking about social conditions which I have experienced up close. I think of this nudity as a feminist cry of Iranian art; it is a way of expressing freedom from traditions and rules that kept us women indoors.” At the same time, she elaborates, “I put ancient Persian patterns on the tiles as a way to localize the figure in my paintings.”

Vahid Sharifian, often described as the Jeff Koons of Tehran, goes even further, creating digital photographs in which he inserts himself, nude, in exotic scenes. In his “Queen of the Jungle” series (2007–8), he can be seen posing spread-eagle in front of a waterfall or stretched out like an odalisque before an elaborate fountain. More startlingly, Shirin Fakhim makes assemblages out of found objects that become effigies of the prostitutes in the streets of Tehran.

“People were really stunned, not only by the work itself but by the fact that this work was being made by an Iranian female artist living in Tehran,” says Rebecca Wilson, curator at the Saatchi Gallery, who featured the work in the “Unveiled” show. “Fakhim’s extraordinarily bold take on prostitution in Tehran, something we hear little about in the West, was an eye-opener to us and everyone visiting the exhibition. There’s a wonderful sense of the absurd in these works pointing at the hypocrisy of the sex industry.”

Governments like Iran’s “have a very strict interpretation of Shiite Islam, but that doesn’t mean that the people themselves are upholders of that same interpretation; if anything, many of them are in opposition to that,” says Sam Bardaouil, curatorial director of Art Reoriented, a company that plans exhibitions about and in the Middle East, including this year’s “Told/Untold/Retold” at Mathaf, the new Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha. “Continually referencing nudity and other secular manifestations in their art,” the curator notes, “is one way of asserting a lineage or continuity in an artistic tradition that has always existed in that part of the world. In a way, that highlights how odd this particular regime is, and how transient.”

The most notorious instance of religious backlash in response to a painting did not take place in Iran, but in India, when M. F. Hussain, the country’s most famous painter and a Muslim, portrayed nude Hindu female deities. After a decade of being under attack by Hindu fundamentalists, subject to lawsuits and death threats, he left the country in 2006 to live in Dubai and London. Last February he was granted citizenship by Qatar.

At the same time, Pakistani artist Rashid Rana has had his controversial “Veil” series exhibited, but only in discreet settings. In these pieces Rana digitally stitched together thumbnail pieces of pornographic images to create an overall picture of a woman in a chador. “I was looking at clichés and paradoxes,” he explains. “Whenever there is a mention of the Muslim world in the Western media, then the image of a veiled woman is shown, especially post-9/11. In contrast, because of easy access to pornography, men in my part of the world have a very distorted image of the Western woman. They imagine that if they would land in Europe or America, there would be people having sex in the parks.” Conflating these two stereotypes resulted in Rana’s highly provocative portrayals, which have been withdrawn from shows, exhibited only in back rooms, and even yanked from sales at international auction houses, in Hong Kong and then New York.

In many cases, Rana points out, these obstacles more often reflect self-censorship rather than outright governmental suppression. Sometimes it is the dealers who are wary. “I didn’t want to exhibit the work publicly in Pakistan for fear of the media making a story out of it,” says Rana. “The people in the art world would not be shocked or upset, but I don’t want trouble from extremists, no matter how few.”

But there are signs, even in the Middle East, of liberalization. In 2008, Lebanese poet Joumana Haddad founded Jasad, a magazine that, according to its website, “aims to reflect the body in all its representations, symbols and projections in our culture, time and societies, and hopes, by doing so, to contribute in breaking the obscurantist taboos.” Its most recent issue featured the oil paintings of Dina El Gharib and Halim Jurdak, explicit photo portraits by Tariq Dajani and works by Western photographers Herb List and Rudolph Lehnert.

Owing to their colonial history, Egypt and Lebanon have a historic relationship with European art movements, especially Surrealism. They traditionally featured nudes in their modernist periods; then contemporary artists followed in their footsteps.

Central Asia, which, by contrast, has its own unique practice of Islam, and is experiencing a renaissance as it emerges from Soviet influence, has also spawned artists who incorporate the body into their work. Among the most notable are Almagul Menlibayeva, whose video

Apa (2003) shows nude women dancing through snowy mounds in a 21st-century vision of earth mothers, and Erbossyn Meldibekov, who sits naked in his video

Pastan (2001), as he is continually slapped by a clothed aggressor in an allusion to his native Kazakhstan’s relationship with the former Soviet Union. “It is not like the nude is a central focus,” says independent curator Leeza Ahmady, “but like in China in the 1990s, artists have begun experimenting in Central Asia in recent years, and the body became a very natural place to start.”

In fact, China exemplifies a revolution in regard to nudity in art, in spite of government censorship and strict control of images deemed pornographic. “Things have relaxed,” says art historian and curator Britta Erickson, “but still, about ten years ago the government reaffirmed a ban on performances in the nude.” She adds, “It also is different for men and for women. Somehow Chinese art society accepts male artists baring themselves, but not female artists.” Erickson notes, “There is no similar taboo or censorship of representations of the nude, so long as sexual activity is not depicted.”

In the course of 5,000 years of Chinese classical art, the nude was rarely depicted. Then, in the 1990s, performance artists such as Zhang Huan and Ma Liuming rebelled against repression by engaging in boldly naked acts, including Zhang Huan, covered in fish oil and honey, sitting in a latrine as flies gathered on his skin, and Ma Liuming prancing nude along the Great Wall. Today, photographer and sculptor Xiang Jing makes 12-foot-tall sculptures of ordinary-looking young women, nude or in their underwear. Chi Peng, a young photographer, created a series of digital images in which he is seen streaking across the streets of Beijing and another series, titled “I Fuck Me,” in which he makes love to his doppelgänger in a phone booth. Even a news announcer, Ou Zhihang, has garnered world attention for photographing himself in the nude performing push-ups at the sites of political controversies, such as the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing.

“In the most recent decade, it all syncs up with further sexual liberation, coupled with the single-child generation due to the one-child policy, together with the consumer revolution and access to the Internet,” says Defne Ayas, China curator for Performa, the New York–based performance-art biennial. “We start seeing an intense line of artistic production that is more influenced by Ryan McGinley, Terry Richardson, Gus Van Sant, and Wolfgang Tillmans than the Song dynasty,” she says.

Barbara Pollack is a contributing editor of ARTnews.

Her book The Wild, Wild East: An American Art Critic’s Adventures in China

was released in April.

Via

ARTnews